I was thrilled when Eddie Huang’s new memoir Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir was tossed on my desk to do a book review. Anyone who has grown up in or around FOB (Fresh Off the Boat) Asian communities has seen first-hand the effects that this tug-o-war of Asian bullying has on kids growing up in this country, but it’s rare to see this side-effect of Asian immigration actually depicted in books, movies, and TV shows.

Where I come from, someone who grows up with multiple cultures is said to have a foot in both worlds. With booming Asian immigration, Asian children growing up in America have one foot in Asia and one foot in America, straddling a delicate line between tradition and stereotypes. On one side they have expectations from fobby Asian parents trying to give their children a better life while maintaining the rich traditions of their homelands; on the other, they are pulled toward a rice-paper Pandora’s Box of Asian stereotypes.

The perpetual foreigner. The martial arts expert. The model minority. The nerd. The geek. The dork. The exotic sexual temptress. The emasculated male. The creepy porn guy. The subservient bit part. The mystic. The dragon villain. The yellowface caricature. The kowtowing, willing recipient of racist, vitriolic hatred. These are all pictures of Asian bullying on the neat little rice-paper box that American media expects Asians to fold themselves into.

Welcome to the everyday reality faced by the children of fobby Asian immigrants.

If you’re familiar with Eddie’s name, you’re probably like me and watch a little too much Food Network. Eddie first rose to the public eye after bringing modernized Chinese cuisine to a cooking competition on the network, and after a controversial loss opened the wildly popular Baohaus restaurant in New York, which has gone on to be featured in numerous shows and magazines on its own. He’s also a trained lawyer and former pot dealer with an impressively diverse résumé.

But as delicious as his food is, I’m a nerd at heart and it was his refreshingly raw, brutally honest account of growing up with immigrant parents that impressed me more than anything else.

Eddie’s story begins with a ruthless retelling of the scene that haunts every Asian kid’s memory of his time in school: eating Asian food at lunch. “Every day I got sent to school with Chinese lunch,” he says. “[…] every day it smelled like shit. I didn’t care about the smell, since it was all I knew, but no one wanted to sit with the stinky kid.” He tells of cruel taunting, Asian bullying, and ching-chong jokes, begging his fobby Asian mother to send him with sandwiches and Capri Sun in a desperate attempt to fit in and pass as white.

“I wanted to be white so fucking bad.”

How many of my readers know what the feeling is like, that feeling of always being on the outside, of never being welcomed as an equal?

He goes on to discuss issues familiar to every Asian kid… Harsh discipline. Finding his place in American pop culture. Trying to insert himself into American mainstays like football. Attempting to join the white crowd and being rejected at every attempt. Growing to hate whiteness and everything it represents in retaliation for a lifetime of rejection and maltreatment.

And, finally, realizing that he’ll never be white, but that his attempts to fit in have rendered him “a loud-mouthed, brash, broken Asian who had no respect for authority in any form, whether it was a parent, teacher, or country.”

That’s a harsh epiphany to reach at such a young age, but it’s a more common reality facing the increasing crowds from Asian immigration than people who are isolated from the fobby Asian community would like to think. Eddie’s book could have ended there and it would still have resonated with Asian youth across the nation, but his story wasn’t over and he had yet to achieve success and redemption.

What struck me the most in this book, more than any other section, was when Eddie began finding his voice as a Chinese-American man in college and started to embrace rather than reject his heritage. He tells a story of joining an Asian club at his university, only to be disgusted that they settled for a whitewashed presentation of Chinese culture and didn’t fight more strongly for their heritage.

“[…] these Uncle Chans convinced us to assimilate, shut the fuck up, and play the part. What they didn’t understand is that after you have the money and degrees, you can’t buy your identity back. I wasn’t worried about degrees, but I cared about my roots. Even if I hated what it meant to be Asian in the American wilderness, I respected the Chinese home I was raised in. Usually I wasn’t so vocal about Asian identity, but without my parents around, I felt a sudden duty to say something myself.”

America is widely hailed as a melting pot, but does that mean an open and accepting environment, or fobby Asians being forced to assimilate?

That… is utterly beautiful.

But it also represents the very real situation facing most Asian children in this country. When confronted with familial expectations and Hollywood’s own Pandora’s Box of Chineseness, you can choose to assimilate. You can choose to play the part dealt to you by Asian immigration and let other people dictate the direction of your life, whether you like it or not. You can break your fingers learning to play the piano. You can break your spirit forcing yourself into medical school, even if you despise it. You can force yourself to play someone else’s game and be something you’re not.

Or you can choose your own direction.

It was choosing his own direction and taking control of his own steering wheel that brought Eddie’s name into the limelight. After a brief attempt at continuing to play someone else’s game and becoming a lawyer, he writes that he began to more fully embrace food as his passion and calling, only to have his rightful win in a Food Network cook-off stolen away and given to a more marketable (and whiter) face.

Let’s pause and be real for a moment.

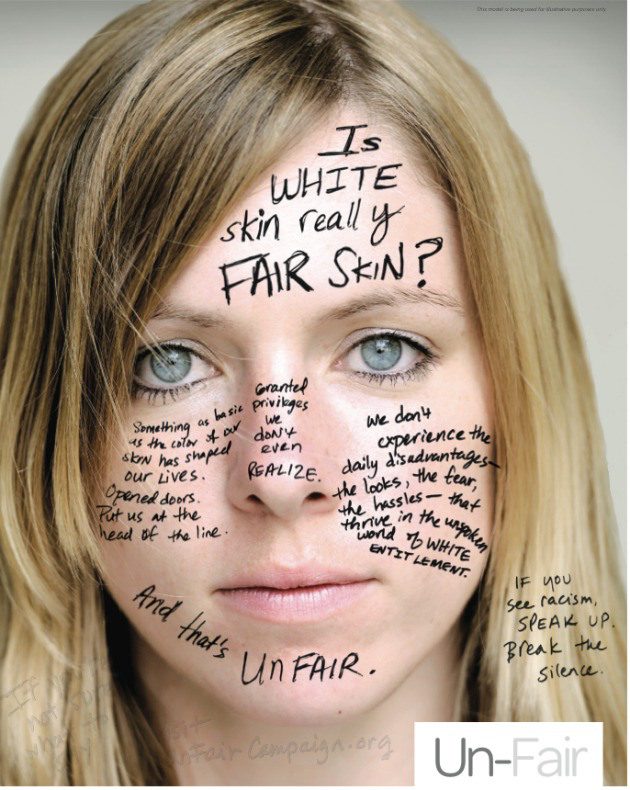

Whether we like to admit it or not, white privilege is very real.

As a white woman, I’ll never know what it’s like to have something taken away from me because I’m not marketable. I am THE definition of marketable. But I have lived and worked in an Asian community for the majority of my life, and I’ve seen it happen time and time again. The reality of Eddie’s absolutely undisguised admission that he’s faced this most basic and cruel form of discrimination, even as a supposedly “lucky” model minority, paints an incredibly shocking and all-too-real picture of what life is like as an Asian-American. He isn’t just writing the memoir of Eddie Huang; he’s writing the memoir of every Asian kid ever born to fobby Asian parents.

At this point in the book, the reader is struck by just how unfair life can be. Asian readers will nod their head in recognition, while white readers will be delivered a cold, hard dose of reality about their own racial privilege.

But part of fighting the good fight against Asian bullying is not giving up, and though only a few pages remained in the book, I was crossing my fingers and toes that Eddie would tell the story about his restaurant. Yes – the guy who was delivered a humiliatingly unfair defeat in a televised cooking competition turned around and opened his own restaurant.

Eddie writes that his mission in opening Baohaus was to bring real Chinese food to the people and represent a positive image of his food and culture. “My main objective with Baohaus was to become a voice for Asian Americans,” he said. “Whether you accept it or not, when you’re a visible Asian you have a torch to carry because we simply don’t have any other representation.”

And that’s the truth. That’s completely and utterly real.

Baohaus is now a wildly successful restaurant and Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir is itself in the works of becoming a new television series (cross your fingers, the “Fresh Off the Boat” pilot’s been sent to the ABC network for review!), and I think that as people affiliated with the Asian community we need to lend our support to this book and the potential sitcom in front of it.

Nowhere else are Asians being given a voice like this.

Nowhere else are Asian Americans having the strength to speak up and smash the model minority myth.

Nowhere else is anyone discussing the realities of life with fobby Asian parents with such stark truth.

Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir is an incredibly well-written piece that bridges the gap for people who grew up with one foot in Asia and one foot in America. Eddie Huang hides absolutely nothing and speaks with brutal honesty when he dissects the experiences that shaped his childhood. At times his words are funny. At times they’re illuminating, cruelly stinging, and even sarcastic. At times they touch a raw nerve we don’t even want to admit exists.

But if you’re looking for a truthful, honest, unashamedly real account of what it’s like to live and grow up as the child of immigrant parents, you’re looking for Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir